Home

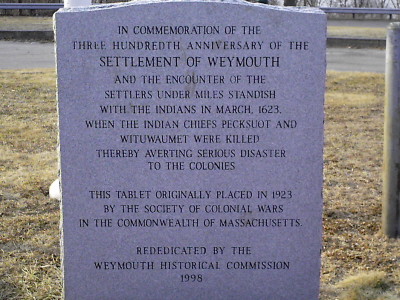

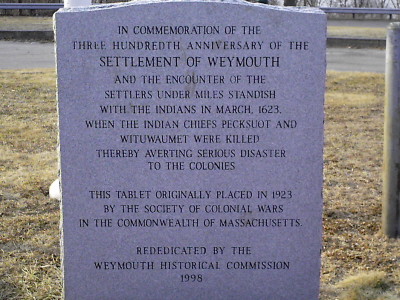

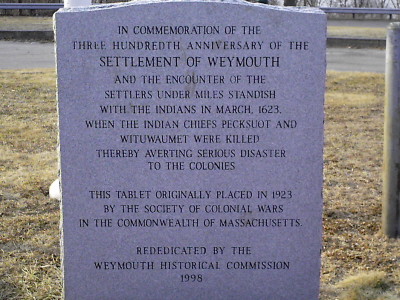

The words on the monument speak for themselves

Treachery Commemorated

After posting this, I received the following Email from a descendent of Standish:

May 31, 2008

Dear Dr. Paul:

Thank you for posting that article about the Real Thanksgiving, and the role of Myles Standish in early Plymouth. I am a descendent of Standish and it has been my goal to understand him and the events concerning him in a deeper way. I want to know ALL the history. I’ve read the WASP approved version and it’s good to see the other versions coming to light.

I work very closely with my ancestors and live my life to redeem their blood. A better knowing of the results of their actions helps in two ways; it clears the propaganda and glamour from my eyes and it inspires me to be a better person in my daily decisions and living. It also teaches me history. Which I wasn’t very good at in high school. Now it has a whole new meaning as I think about my ancestors living in those times and places. My nieces and nephews will learn the truth from me. And their children too.

For what its worth, I apologise for my grandfathers actions. Indeed all my ancestors.

Respectfully and sincerely,

Clarence Standish, IV

The Real Thanksgiving

Quoted from: The Hidden History of Massachusetts

Much of America's understanding of the early relationship between the Indian and the European is conveyed through the story of Thanksgiving. Proclaimed a holiday in 1863 by Abraham Lincoln, this fairy tale of a feast was allowed to exist in the American imagination pretty much untouched until 1970, the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. That is when Frank B. James, president of the Federated Eastern Indian League, prepared a speech for a Plymouth banquet that exposed the Pilgrims for having committed, among other crimes, the robbery of the graves of the Wampanoags. He wrote:

"We welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people."

But white Massachusetts officials told him he could not deliver such a speech and offered to write him another. Instead, James declined to speak, and on Thanksgiving Day hundreds of Indians from around the country came to protest. It was the first National Day of Mourning, a day to mark the losses Native Americans suffered as the early settlers prospered. This true story of "Thanksgiving" is what whites did not want Mr. James to tell.

What Really Happened in Plymouth in 1621?

According to a single-paragraph account in the writings of one Pilgrim, a harvest feast did take place in Plymouth in 1621, probably in mid-October, but the Indians who attended were not even invited. Though it later became known as "Thanksgiving," the Pilgrims never called it that. And amidst the imagery of a picnic of interracial harmony is some of the most terrifying bloodshed in New World history.

The Pilgrim crop had failed miserably that year, but the agricultural expertise of the Indians had produced twenty acres of corn, without which the Pilgrims would have surely perished. The Indians often brought food to the Pilgrims, who came from England ridiculously unprepared to survive and hence relied almost exclusively on handouts from the overly generous Indians-thus making the Pilgrims the western hemisphere's first class of welfare recipients. The Pilgrims invited the Indian sachem Massasoit to their feast, and it was Massasoit, engaging in the tribal tradition of equal sharing, who then invited ninety or more of his Indian brothers and sisters-to the annoyance of the 50 or so ungrateful Europeans. No turkey, cranberry sauce or pumpkin pie was served; they likely ate duck or geese and the venison from the 5 deer brought by Massasoit. In fact, most, if notall, of the food was most likely brought and prepared by the Indians, whose 10,000-year familiarity with the cuisine of the region had kept the whites alive up to that point.

The Pilgrims wore no black hats or buckled shoes-these were the silly inventions of artists hundreds of years since that time. These lower-class Englishmen wore brightly colored clothing, with one of their church leaders recording among his possessions "1 paire of greene drawers." Contrary to the fabricated lore of storytellers generations since, no Pilgrims prayed at the meal, and the supposed good cheer and fellowship must have dissipated quickly once the Pilgrims brandished their weaponry in a primitive display of intimidation. What's more, the Pilgrims consumed a good deal of home brew. In fact, each Pilgrim drank at least a half gallon of beer a day, which they preferred even to water. This daily inebriation led their governor, William Bradford, to comment on his people's "notorious sin," which included their "drunkenness and uncleanliness" and rampant "sodomy"...

The Pilgrims of Plymouth, The Original Scalpers

Contrary to popular mythology the Pilgrims were no friends to the local Indians. They were engaged in a ruthless war of extermination against their hosts, even as they falsely posed as friends. Just days before the alleged Thanksgiving love-fest, a company of Pilgrims led by Myles Standish actively sought to chop off the head of a local chief. They deliberately caused a rivalry between two friendly Indians, pitting one against the other in an attempt to obtain "better intelligence and make them both more diligent." An 11-foot-high wall was erected around the entire settlement for the purpose of keeping the Indians out.

Any Indian who came within the vicinity of the Pilgrim settlement was subject to robbery, enslavement, or even murder. The Pilgrims further advertised their evil intentions and white racial hostility, when they mounted five cannons on a hill around their settlement, constructed a platform for artillery, and then organized their soldiers into four companies-all in preparation for the military destruction of their friends the Indians.

Pilgrim Myles Standish eventually got his bloody prize. He went to the Indians, pretended to be a trader, then beheaded an Indian man named Wituwamat. He brought the head to Plymouth, where it was displayed on a wooden spike for many years, according to Gary B. Nash, "as a symbol of white power." Standish had the Indian man's young brother hanged from the rafters for good measure. From that time on, the whites were known to the Indians of Massachusetts by the name "Wotowquenange," which in their tongue meant cutthroats and stabbers.

Who Were the "Savages"?

The myth of the fierce, ruthless Indian savage lusting after the blood of innocent Europeans must be vigorously dispelled at this point. In actuality, the historical record shows that the very opposite was true.

Once the European settlements stabilized, the whites turned on their hosts in a brutal way. The once amicable relationship was breeched again and again by the whites, who lusted over the riches of Indian land. A combination of the Pilgrims' demonization of the Indians, the concocted mythology of Eurocentric historians, and standard Hollywood propaganda has served to paint the gentle Indian as a tomahawk-swinging savage endlessly on the warpath, lusting for the blood of the God-fearing whites.

But the Pilgrims' own testimony obliterates that fallacy. The Indians engaged each other in military contests from time to time, but the causes of "war," the methods, and the resulting damage differed profoundly from the European variety:

o Indian "wars" were largely symbolic and were about honor, not about territory or extermination.

o "Wars" were fought as domestic correction for a specific act and were ended when correction was achieved. Such action might better be described as internal policing. The conquest or destruction of whole territories was a European concept.

o Indian "wars" were often engaged in by family groups, not by whole tribal groups, and would involve only the family members.

o A lengthy negotiation was engaged in between the aggrieved parties before escalation to physical confrontation would be sanctioned. Surprise attacks were unknown to the Indians.

o It was regarded as evidence of bravery for a man to go into "battle" carrying no weapon that would do any harm at a distance-not even bows and arrows. The bravest act in war in some Indian cultures was to touch their adversary and escape before he could do physical harm.

o The targeting of non-combatants like women, children, and the elderly was never contemplated. Indians expressed shock and repugnance when the Europeans told, and then showed, them that they considered women and children fair game in their style of warfare.

o A major Indian "war" might end with less than a dozen casualties on both sides. Often, when the arrows had been expended the "war" would be halted. The European practice of wiping out whole nations in bloody massacres was incomprehensible to the Indian.

According to one scholar, "The most notable feature of Indian warfare was its relative innocuity." European observers of Indian wars often expressed surprise at how little harm they actually inflicted. "Their wars are far less bloody and devouring than the cruel wars of Europe," commented settler Roger Williams in 1643. Even Puritan warmonger and professional soldier Capt. John Mason scoffed at Indian warfare: "[Their] feeble manner...did hardly deserve the name of fighting." Fellow warmonger John Underhill spoke of the Narragansetts, after having spent a day "burning and spoiling" their country: "no Indians would come near us, but run from us, as the deer from the dogs." He concluded that the Indians might fight seven years and not kill seven men. Their fighting style, he wrote, "is more for pastime, than to conquer and subdue enemies."

All this describes a people for whom war is a deeply regrettable last resort. An agrarian people, the American Indians had devised a civilization that provided dozens of options all designed to avoid conflict--the very opposite of Europeans, for whom all-out war, a ferocious bloodlust, and systematic genocide are their apparent life force. Thomas Jefferson--who himself advocated the physical extermination of the American Indian--said of Europe, "They [Europeans] are nations of eternal war. All their energies are expended in the destruction of labor, property and lives of their people."

Puritan Holocaust

By the mid 1630s, a new group of 700 even holier Europeans calling themselves Puritans had arrived on 11 ships and settled in Boston-which only served to accelerate the brutality against the Indians.

In one incident around 1637, a force of whites trapped some seven hundred Pequot Indians, mostly women, children, and the elderly, near the mouth of the Mystic River. Englishman John Mason attacked the Indian camp with "fire, sword, blunderbuss, and tomahawk." Only a handful escaped and few prisoners were taken-to the apparent delight of the Europeans:

To see them frying in the fire, and the streams of their blood quenching the same, and the stench was horrible; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave praise thereof to God.

This event marked the first actual Thanksgiving. In just 10 years 12,000 whites had invaded New England, and as their numbers grew they pressed for all-out extermination of the Indian. Euro-diseases had reduced the population of the Massachusett nation from over 24,000 to less than 750; meanwhile, the number of European settlers in Massachusetts rose to more than 20,000 by 1646.

By 1675, the Massachusetts Englishmen were in a full-scale war with the great Indian chief of the Wampanoags, Metacomet. Renamed "King Philip" by the white man, Metacomet watched the steady erosion of the lifestyle and culture of his people as European-imposed laws and values engulfed them.

In 1671, the white man had ordered Metacomet to come to Plymouth to enforce upon him a new treaty, which included the humiliating rule that he could no longer sell his own land without prior approval from whites. They also demanded that he turn in his community's firearms. Marked for extermination by the merciless power of a distant king and his ruthless subjects, Metacomet retaliated in 1675 with raids on several isolated frontier towns. Eventually, the Indians attacked 52 of the 90 New England towns, destroying 13 of them. The Englishmen ultimately regrouped, and after much bloodletting defeated the great Indian nation, just half a century after their arrival on Massachusetts soil. Historian Douglas Edward Leach describes the bitter end:

The ruthless executions, the cruel sentences...were all aimed at the same goal-unchallengeable white supremacy in southern New England. That the program succeeded is convincingly demonstrated by the almost complete docility of the local native ever since.

When Captain Benjamin Church tracked down and murdered Metacomet in 1676, his body was quartered and parts were "left for the wolves." The great Indian chief's hands were cut off and sent to Boston and his head went to Plymouth, where it was set upon a pole on the real first "day of public Thanksgiving for the beginning of revenge upon the enemy." Metacomet's nine-year-old son was destined for execution because, the whites reasoned, the offspring of the devil must pay for the sins of their father. The child was instead shipped to the Caribbean to spend his life in slavery.

As the Holocaust continued, several official Thanksgiving Days were proclaimed. Governor Joseph Dudley declared in 1704 a "General Thanksgiving"-not in celebration of the brotherhood of man-but for [God's] infinite Goodness to extend His Favors...In defeating and disappointing... the Expeditions of the Enemy [Indians] against us, And the good Success given us against them, by delivering so many of them into our hands...

Just two years later one could reap a ££50 reward in Massachusetts for the scalp of an Indian-demonstrating that the practice of scalping was a European tradition. According to one scholar, "Hunting redskins became...a popular sport in New England, especially since prisoners were worth good money..."

References in The Hidden History of Massachusetts: A Guide for Black Folks ©© DR. TINGBA APIDTA, ; ISBN 0-9714462-0-2

For purchase details Email A. Muhammad "mghemlf@att.net"

********************

During March 1623 Myles Standish lured two Chiefs to a meeting then murdered them. The picture of the monument, erected by the Weymouth Historical Commission, depicts how the town of Weymouth, Mass, takes pride in his barbaric deed.

What Hellish Pride and Prejudice

What in hell is a hearth built on blood of a brother’s harvest you absconded, along with a curve of land kissed by ocean for first people given this fine land, who were sickened on your flu-filled flannel gifts until they were too weak to wise on to your malicious plans?

You merchant-adventurers of Weymouth, mount your monument of treason against corn-fed Wessagusset, as you celebrate 300 years of your encroachment on eternity’s placement of a people who had heroes like Pecksuot who, even thirty years ago, still, is said, tucked a child into her covers at Bricknell house so she did not have to see your scurrilous skirmishes.

You promote your pestilent importance on this land, as if you thought you would be allowed to stay forever. You hold a fatal flaw in this grasp to make it seem you made something worthy.

What is worthier than Wampanoag in first light, who had their blood spilled by you, on the very ground you grind against?

Listen, they speak, and trace truthful steps through and around this place you think you own: Such pride and prejudice in this piece of cement that will not outlast us, the true people of the East, or sun that burns red on mornings it remembers.

Carol Desjarlais

*******************

New York Times

November 25, 2004

Banned in Boston: American Indians, but Only for 329 Years

By KATIE ZEZIMA

BOSTON, Nov. 24 - It is a prejudicial, archaic concept that prohibited Native Americans from entering a city for fear members of their "barbarous crew" would cause residents to be "exposed to mischief."

But it is more than notions and phrases in Boston. A ban on Indians entering Boston has been the law since 1675.

Mayor Thomas M. Menino took a step toward repealing the ban on Wednesday, filing a home rule petition. Mr. Menino said a repeal would remove the last vestiges of discrimination from a vibrant, diverse city that is looking past old racial conflicts.

"This law has no place in Boston," Mr. Menino said. "Fortunately this act is no longer enforced. But as long as it remains on the books, this law will tarnish our image. Hatred and discrimination have no place in Boston. Tolerance, equality and respect - these are the attributes of our city."

Joanne Dunn, executive director of the Boston Native American Center, said she laughed a bit as she drove into Boston on Wednesday, realizing that she was, technically, breaking the law (being without benefit of the "two musketeers" required to escort American Indians with business in the city). "For us indigenous people it brings some closure," Ms. Dunn said. "You come into the City of Boston and it crosses your mind that you're not welcome here."

The Boston City Council, which in April 2003 unanimously passed a resolution calling for repeal, must now approve the petition to remove the ban. The repeal must then pass the legislature and be signed by Gov. Mitt Romney.

A spokeswoman for Robert E. Travaglini, the president of the State Senate, said Mr. Travaglini had not seen the petition and would allow the City Council to act before considering action. A spokeswoman for Mr. Romney, a Republican, said he had not seen the petition either and would be "happy to take a look at it" when it crossed his desk.

Felix Arroyo, a city councilman, said he expected the measure to pass unanimously at a council meeting on Dec. 1. "I think all of us will look forward to voting yes on this," Mr. Arroyo said.

The Massachusetts General Court enacted the law, called the Indian Imprisonment Act, in 1675. The legislation came at the height of King Philip's War, a conflict between the Wampanoag tribe, led by Metacom, known as Philip, and settlers near Plymouth, Mass. The war began in 1675 with a raid on the town of Swansea and spread across Massachusetts, spilling north to New Hampshire and south to Connecticut. The war, one of the bloodiest on American soil, ended the next year.

The law rolled over when the state's Constitution was enacted in 1780 and has lingered for centuries, with no one taking the steps to repeal it. The Muhheconnew National Confederacy, a lobbying group based in Falmouth, Mass., started pushing for repeal in 1996 after working with the city to protect Indian burial grounds on the Boston Harbor islands. The group petitioned the legislature, then the city, and received the necessary resolution last year. It renewed the push in July, before the Democratic National Convention.

"It means a great thing," said Sam Sapiel, 73, a member of the Penobscot Nation of Maine who lives in Falmouth and worked with the Muhheconnew Confederacy on the repeal. "It's what we've been striving for."

It was little coincidence that Mr. Menino signed the petition the day before Thanksgiving. The podium at the news conference was decorated with a splash of crimson chrysanthemums, and the desk Mr. Menino used to sign the petition was festooned with a pumpkin and other gourds. An Indian leader also invoked the holiday.

"Being so close to Thanksgiving, this is a good day for native people," said Beverly Wright, a member of the Wampanoag tribe of Martha's Vineyard, the state's only federally recognized tribe. "It's been on the books for a long time."

Ms. Wright believes there might be other, similarly discriminatory laws. Mr. Menino said he would look into the possibility of repealing them.

Please click to read about The Doctrine of Discovery: http://www.danielnpaul.com/DoctrineOfDiscovery.html

Please click to read about Christopher Columbus: http://www.danielnpaul.com/ChristopherColumbus.html

Quoted from a 2010 Interview:

Alex Doherty: You have claimed that a close parallel to the conquest of America is the Nazi invasion of Eastern Europe. To many that will seem an outlandish and even an offensive comparison - can you explain why you think it is apt comparison?

I’m not comparing the events but rather the reaction to them. Here’s my argument I have made: Imagine that Germany had won World War II and that a Nazi regime endured for some decades, eventually giving way to a more liberal state with a softer version of German-supremacist ideology. Imagine that a century later, Germans celebrated a holiday based on a sanitized version of German/Jewish history that ignored that holocaust and the deep anti-Semitism of the culture. Would we not question the distortions woven into such a celebration and denounce such a holiday as grotesque?

Now, imagine that left/liberal Germans -- those who were critical of the power structure that created that distorted history and who in other settings would challenge the political uses of those distortions -- put aside their critique and celebrated the holiday with their fellow citizens, claiming that they could change the meaning of the holiday in private. Would we not question that claim?

Comparisons to the Nazis are routinely overused and typically hyperbolic, but this is directly analogous. When I offer this critique in left/liberal circles, some people acknowledge that the argument is valid but make it clear they will continue to celebrate Thanksgiving. Others get angry and accuse me of posturing. It’s not posturing, but rather a struggle to understand how to live in a culture that cannot tell the truth.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. New Left Project’s Alex Doherty talked to him about Thanksgiving, the murder of indigenous people and the theft of their land by European colonialists.

BACK HOME WEB SITE MAP